“A really good picture looks as if it’s happened at once. It’s an immediate image … it looks as if it were born in a minute.” Helen Frankenthaler

It is a feat to make something that requires utmost skill look as though it came about through no effort at all, that it just happened naturally by some beautiful coincidence. Such a feat is embodied in the 36 woodcut prints by American artist Helen Frankenthaler on show at Dulwich Picture Gallery. Each one is overtly painterly, some almost watercolour-esque, turning an ordinarily rigid medium entirely upside down. Yet there is more than effortlessness on display here. Laid bare, too, is the beauty of the process – collaboration, innovation, trial, error and discovery. We are reminded, or perhaps enlightened, that Frankenthaler was a fearless experimenter not just in paint, but in print too.

East and beyond (1973) (fig 1), Frankenthaler’s first foray into woodcuts, commences the exhibition. Its title attests to woodcut printing’s Eastern origins and the significance of the region throughout Frankenthaler’s printing journey. Innovating from the get-go, Frankenthaler used a jigsaw to produce the composition, which appears minimal at first glance, however, reveals surprising intricacy in shape, line and colour when viewed more closely. Situated next to it is Geisha, made 30 years later in 2003. By this point Frankenthaler had invented techniques such as “guzzying”, where she would distress her surfaces with various tools for differing effects. Geisha is much looser than its neighbour; it has an organic feel with more visible woodgrain and earthy tones, looking as if born from nature without human intervention. The shape that graces the centre of the composition, ambiguous yet seductive and bodily, holds a subtle, kinetic energy akin to an aqueous substance that has been left to ooze down a vertical plane. This 23-colour work used 15 woodblocks and took Frankenthaler a year to make. Effort was spent here, but Geisha is not burdened visually by this – Frankenthaler creates a mirage of spontaneity.

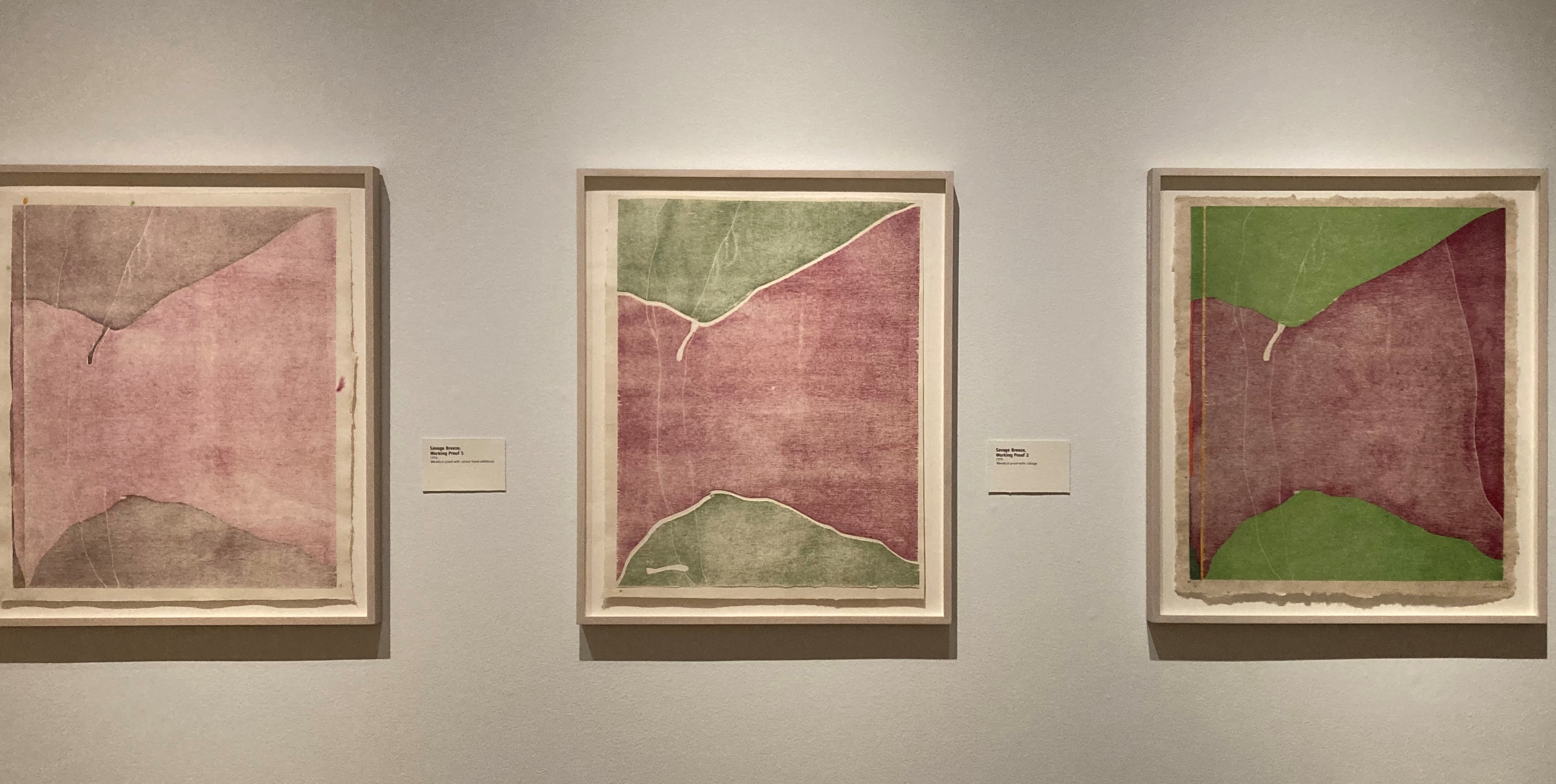

The display of elaborate maquettes and working proofs draws attention to Frankenthaler’s significant efforts to reach her final compositions. Savage Breeze (1974), an eight-colour woodcut, is exhibited with two working proofs. Their display together visualises an evolution of experimentation, showing variations and progression, with the final print bearing the greatest richness of colour and sense of light. All three are wonderful, but the chosen one has a distinct cohesion that unites the red and green elements together with ease. Making this print was a trial for Frankenthaler – “it went dead like a lead balloon … I was almost exasperated” she described, and yet, she persisted. Viewing the three prints together allows us to gain an understanding of Frankenthaler’s relentless ambition to achieve the outcome she desired. Their display also serves as a reminder to us all that, oftentimes, behind those superficially flawless images that bombard us in the modern world lies significant preparation and exertion.

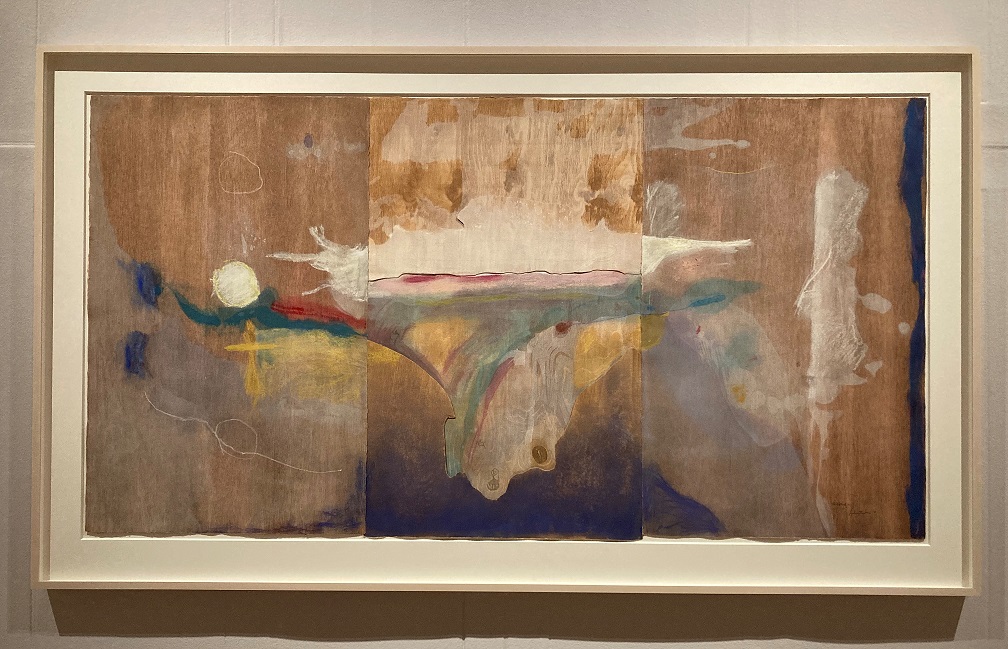

The exhibition ends with a room dedicated to Madame Butterfly, Frankenthaler’s “woodcut masterpiece”. Years of experimentation and numerous collaborations with printing experts in both America and Japan culminate in a work of ethereality. Watercolour-like swathes of rainbow hues and white sweep across imprinted wood grain, with the wood’s natural lines aiding a sense of lyricism. The paint imbues into the grain in places, intermingling them together as one and creating a similar sense of naturality as seen in Geisha. The print is situated in the gallery flanked by a painting and a working proof of the composition (fig 4), creating an immersive viewing experience and, once again, evidencing Frankenthaler’s extensive and time-consuming processes to reach a finale that satisfied her. With the same name as the inimitable Puccini opera, a tragedy surrounding a geisha and her fateful marriage to an American lieutenant, themes of love and death might be ascertained. However, Frankenthaler’s forms are ambiguous: a rainbow amidst stormy skies, a trickle of blood, the wings of a butterfly. We are invited to find meaning as we wish.

Seeing this exhibition is to bear witness to the transformation of a media that is fundamentally entrenched with the weight of wood into one that can deliver the most delicate, painterly and ephemeral-looking of outcomes. While one could say that the presence of preliminary workings jars her ambition to create an image that ‘looks as if it was born in a minute’, they are revealed to be elaborate objects of beauty in themselves, providing a snapshot into Frankenthaler’s sheer tenacity. Effortlessly beautiful and seemingly spontaneous in their finished state, knowing Frankenthaler’s innovatory journey to bring her woodcut prints to fruition makes them all the more miraculous.

On view until 18 April 2022.