Louise Bourgeois’ sculpture ‘Untitled’ (1996) (fig 1) stands in a corner of the Hayward Gallery like some kind of surrealist washing line. Silk undergarments and a sequined dress suspend from thick animal bones, ghostly forms swaying slightly as visitors pass by. The sculpture is part of ‘The Woven Child’, an exhibition chronicling Bourgeois’ obsession with textiles during the last two decades of her life. Through the medium, she found the means to explore a myriad of topics, from her personal history and family, to aspects of human existence only found in the deepest recesses of the mind.

Of the hanging garments in ‘Untitled’, two are stuffed, giving the impression of human-like, headless bodies eerily cut off at the waist or legs. At the base of the sculpture, the rhyme ‘Seamstress, Mistress, Distress, Stress’ is scribed. Certain themes are clear – sex, death and femininity – but the true impetus for this collection of clothes is deeply personal, with the work alluding to Bourgeois’ father’s affair with the family governess, and the rhyme insinuating an illicit relationship and the collateral, psychological damage inevitably caused. Bourgeois reaped power from textiles, subverting perspectives of a medium habitually regarded as decorative or utilitarian, existing mainly within an outmoded concept of the domestic realm. Her manipulation of fabrics, both in terms of her presentation of personal items which she squirreled away from the past and her physical stitching of new forms, grapple with the mystifying nature of so much of life – Untitled is exemplary of this, contending with our capacity to make self-gratifying choices that will, in all likelihood, hurt the ones we love.

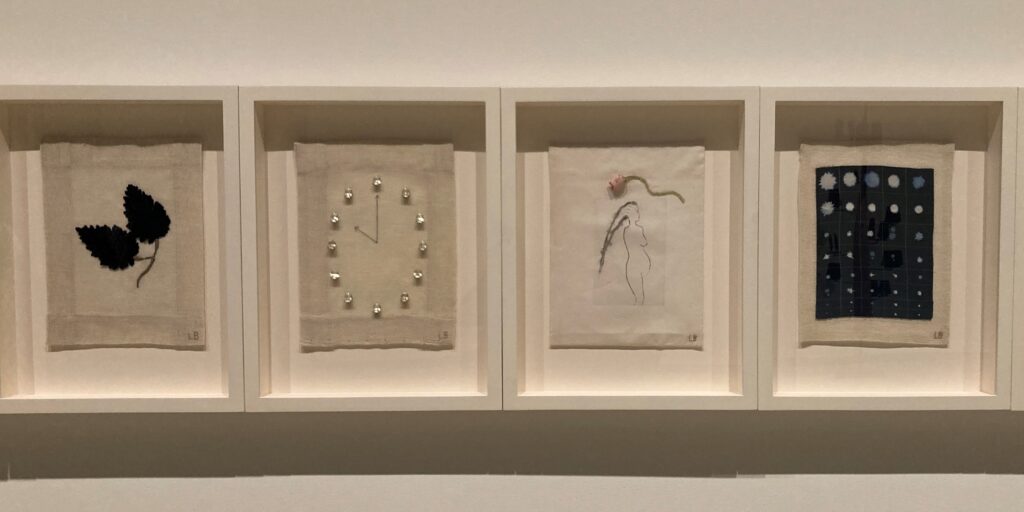

Yet, the domesticity inextricably linked with textiles is by no means rejected by Bourgeois. The biographical nature of her fabric-based work is deeply rooted in memories of her life at home, and textiles’ domestic associations provided both an opportunity to destabilise preconceptions and a ready-made foundation to explore her familial experiences. Eugénie Grandet (2009) (fig 2), for example, features handkerchiefs and tea towels from Bourgeois’ early life in France, kept for over 70 years and adorned with buttons, artificial flowers and beads from her own clothing and sewing box. Comprised of 16 panels, each one quite beautiful and delicately formed, the work references Bourgeois’ relationship with her domineering father, which she felt mirrored the life of the protagonist of Honoré de Balzac’s eminent novel, ‘Eugénie Grandet’. Personal, treasured textiles paired with the physicality of the traditional practice of embroidery and collaging imbue the work with nostalgia and care. Made shortly before Bourgeois died, it is a physical record of her reflecting on the past through the textiles she amassed along the way, in turn acknowledging the inevitable passing of time that is universal to us all.

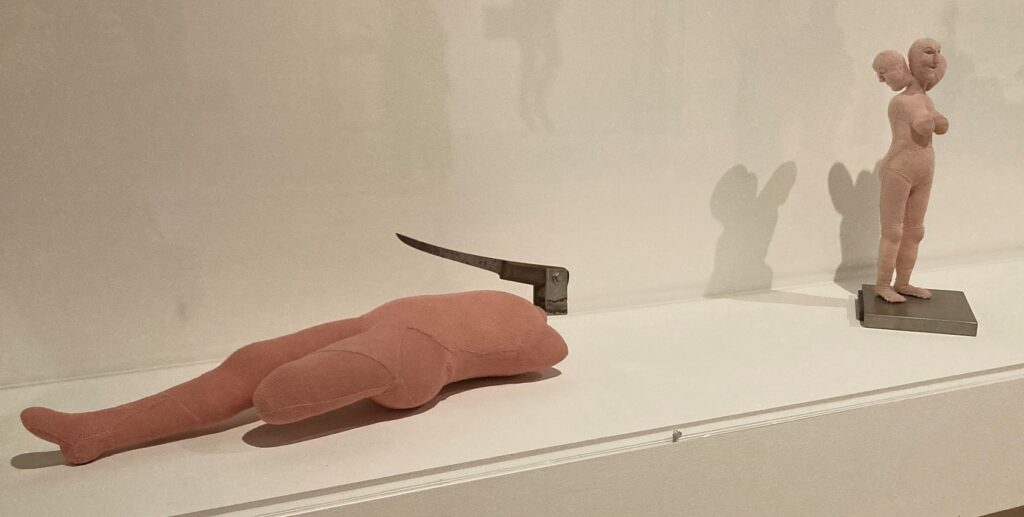

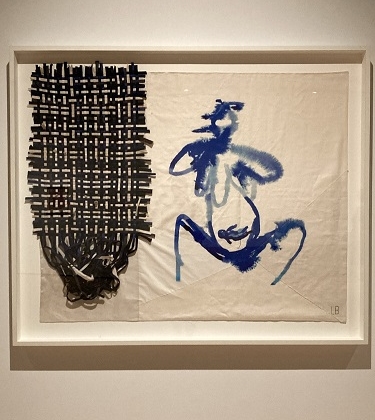

The body features throughout (fig 3 and 4); small, handstitched dolls made from pink fabric, some armless, another with three heads, one with half a leg, a painting of a pregnant woman printed on cloth, the foetus visible inside her bulging stomach. While they retain an unassuming, craft-like aesthetic upon superficial glance, Bourgeois utilised the pliability of textiles to capture the pain and triumphs of humanity – from psychological strife, to the phenomenon of pregnancy. The soft, fleshy dolls are like twisted cousins of children’s toys, one even sports a knife instead of a head, while Bourgeois’ hand stitching, visible at times, is a metaphor for particular mental states – the more erratic the stitches, the more erratic the mind. Any preconceptions of textiles as modest and aesthetically driven become misconceptions in the face of these works.

A giant, circa 3 metre needle curves in a crescent shape in Needle (Fuseau)(1992) (fig 5), its sharp point ready to pierce and stitch with a yarn of flax. Chintz tapestry is the basis for Lady in Waiting (2003) (fig 6), a large wood and glass structure which encases a tapestry chair, where a faceless doll sits with protruding spider legs and threads spilling from where her mouth should be. Then, there is Spider (1997) (fig 7), one of Bourgeois’ huge and formidable steel arachnids, standing over a wire ‘cell’ housing an upholstered chair and covered with pieces of tapestry – a reference to her parents’ tapestry business, through which she found herself embedded in textiles from childhood. The immediate reaction to these works is one of terror, but fear is not at their heart. Rather, for Bourgeois, the web-weaving spider was a sign of creativity and resilience, as well as symbolic of her mother, a weaver herself. Similarly, the needle signified repair, a forgiving tool that could mend, bring together and complete. Through all of the sinister implications on show, Bourgeois’ textile works convey life’s dichotomies – brutal yet reassuring, ephemeral yet resilient, pain and love, the anxiety and angst followed by the relax and release; Spiral Woman (2003) (fig 8) portrays the latter exactly.

Memory attaches to textiles, it weaves its way into the warps and wefts of fabrics that occupy our everyday. Textiles are with us in the moment, they come along for the ride, touching our skin, taking in the air and provide a lasting, tangible memento of both the good and the bad. Textiles can be stitched, stuffed, ripped, repaired, possessing a duality of strength and delicacy – from thick streams of hardy yarn, to a fine silk chemise. Bourgeois, it would seem, was aware of these attributes throughout her life, hoarding various fabric-based items as she manoeuvred her way through the world and utilising textiles’ formal properties to create profound and psychologically-loaded work. As an art form, textiles should not be underestimated, and Bourgeois’ fabric-based pieces, with their ability to both shock and bear a multitude of memories even after her death, is testament to this.

‘Louise Bourgeois: The Woven Child’ was on view at the Hayward Gallery at the Southbank Centre in London from 9 February – 15 May 2022.